Numerous factors, from changes in eating habits to antibiotic treatments, influence the delicate microbial balance and lead to dysbiosis.

Dysbiosis refers to an imbalance in the number or type of microbial colonies that have colonized humans. Evaluating the relationship between the intake of ultra-processed foods, the changes produced in the microbiota and the risk of diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome, is an interesting new field of study.

Alejandro Monzó – Neolife Nutrition Unit

Also called dysbacteriosis, dysbiosis can affect digestion, nutrient absorption, vitamin production, and control of harmful microorganisms.

The term microbiota refers to the set of microorganisms (all bacteria, archaea, eukaryotes, and viruses) present in a given environment, such as the intestinal tract. Scientists define the term microbiome as the entire habitat, including microorganisms, their genes, and external environmental conditions (1).

Endogenous human microbial communities are involved in multiple metabolic, physiological, and immunological functions, which is why any alteration in the function and composition of the microbiome may pose significant health consequences (2). The main functional contributions attributed to the human microbiome are presented below:

- Maintenance of the skin and mucous barrier function

- Food digestion and nutrition

- Energy generation and vitamin production

- Metabolic regulation and control of fat storage

- Processing and detoxification of environmental chemicals

- Differentiation and maturation of the host mucosa and their immune system

- Development and regulation of immunity, helping to maintain the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory processes

- Prevention of invasion and growth of disease-promoting microorganisms

- Contribution to the development and maturation of the nervous system

The human microbiome is mainly defined by two types of bacteria, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, the latter accounting for 90% of the intestinal microbiota and, to a lesser extent, actinobacteria.

New studies show that dysbiosis has been associated with a number of gastrointestinal disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Significant differences have been seen in the microbiota of IBS patients compared to healthy control subjects. Additionally, other research has identified a link between IBS and bacterial overpopulation through the use of breath testing (3).

An individual’s diet is one of the key modulators of gut microbiota composition that directly influences host health and biological processes, but also through metabolites derived from microbial fermentation of nutrients, specifically, short-chain fatty acids (2,3). In this regard, a new study published in the British Medical Journal shows that ultra-processed foods are associated with a higher risk of inflammatory bowel disease (4).

Ultra-processed foods include baked goods, sugary drinks and soft drinks, precooked foods, reconstituted meat and fish products, snacks, and all kinds of packaged foods, which often contain high levels of sugar, salt, additives, and unhealthy fats. These are packed with energy but provide insufficient amounts of nutrients, since they lack vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Inflammatory bowel disease is more common in industrialized countries and the authors point out that dietary factors may be related. Similarly, dietary components and foods can have a major impact on gut microbiota.

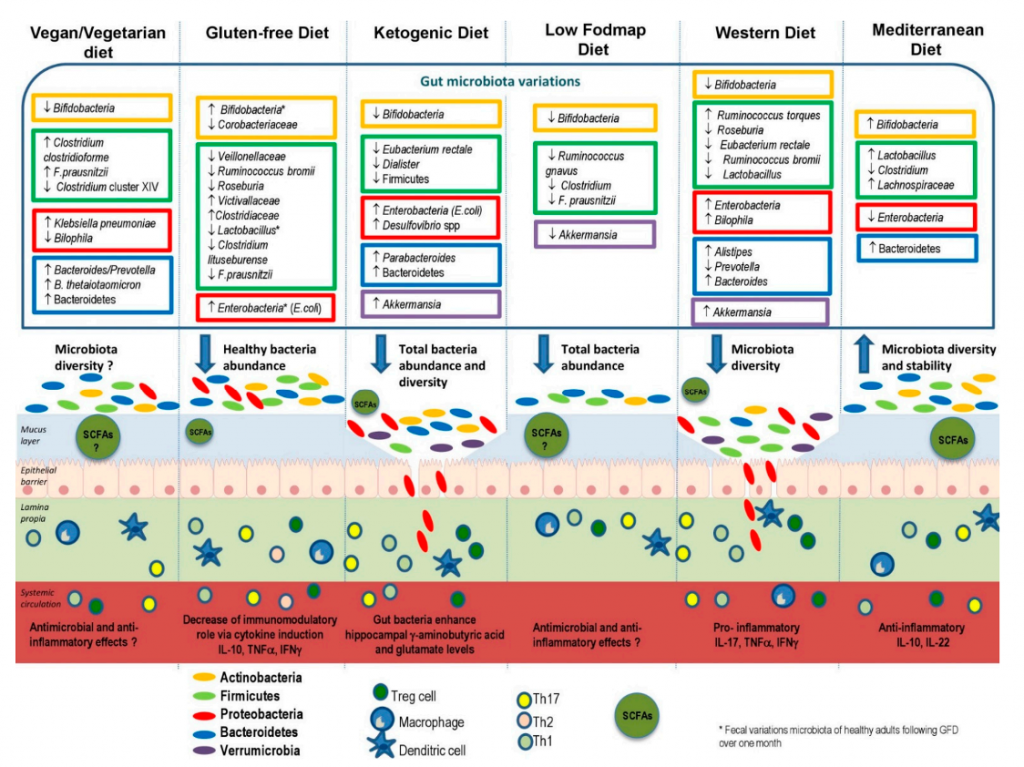

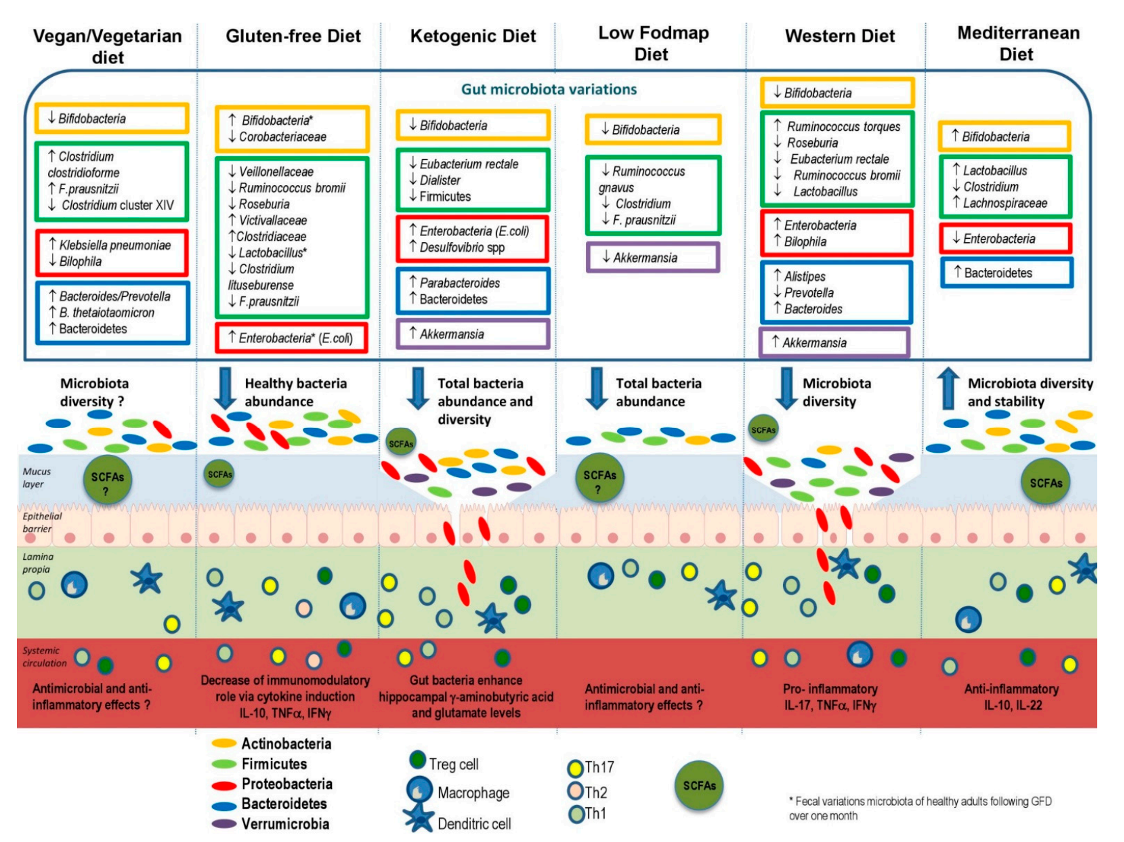

That said, a recent review published in the journal Nutrients discusses new research on how certain diets, as well as food components and additives, affect the composition of the gut microbiota (Figure 1) (5) (5).

The authors indicate that a food variety is better for gut health and promotes a balanced composition of gut microbiota. On the one hand, a high intake of animal proteins, saturated fats, sugars, and salt could stimulate the growth of pathogenic bacteria to the detriment of beneficial bacteria, which may lead to alterations of the intestinal barrier. On the other hand, the consumption of complex polysaccharides and vegetable protein could be associated with an increase in the amount of beneficial bacteria, stimulating the production of short-chain fatty acids. Additionally, polyphenols, omega-3 fatty acids and micronutrients appear to have the potential to confer health benefits through modulation of the gut microbiota (5).

Therefore, a diet rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, and greens promotes a healthy composition of the intestinal microbiota and the intestine. The Western dietary pattern, characterized by a high content of ultra-processed foods, may lead to a decrease in beneficial bacteria, which may increase intestinal permeability and inflammation. Experts agree that the Mediterranean dietary pattern remains the solution to optimally modulate the diversity and stability of the microbiota, as well as the regular permeability and activity of the individual’s immune functions.

The Mediterranean diet, centered on fruits, vegetables, olive oil, nuts, legumes, fish, and whole grains, has been linked to a host of health benefits, including alower risk of mortality and the prevention of many diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cognitive impairment, and depression. It is based on the consumption of essential fatty acids, polyphenols, and other antioxidants, a high intake of prebiotic fiber and low glycemic index carbohydrates, and a higher intake of vegetable proteins than animal proteins. This is a dietary pattern that, ultimately, with its benefits modulates a healthy gut microbiota.

Finally, the journal Medicina Clínica recommends the following measures to prevent and combat dysbiosis (2):

- Maintaining a regular oral hygiene to control the microbiota in the mouth

- Maintaining an adequate body mass index (BMI) to prevent metabolic syndrome by losing weight, controlling blood pressure, and exercising regularly

- Avoiding hydrogenated and saturated fats, prioritizing monounsaturated (olive oil) and polyunsaturated omega-3 (rather than omega-6) fatty acids

- Avoiding the indiscriminate and unjustified administration of antibiotics, as well as the ingestion of meat obtained from animals that have been treated with antibiotics or hormones

- Restricting as much as possible cosmetic products or foods containing molecules of dubious efficacy or recognized toxicity (endocrine disruptors)

Finally, the medical and nutritional team here at Neolife analyzes each of the health factors in each individual case, where the role of the microbiota is of special interest due to the latest scientific evidence regarding its impact on disease prevention. Neolife creates a personalized diet, after completing the microbiota analysis, with the goal of modulating and restoring a healthy intestinal microbiota and providing optimal health results. Future advances in the knowledge of the interactions between food compounds and gut bacteria will lead to a better understanding of both positive and negative interactions with dietary habits.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Gut Microbiota for Health. (2021). “Gut microbiota info”. URL: https://www.gutmicrobiotaforhealth.com/about-gut-microbiota-info/

(2) Chimenos-Küstner, E. et al. (2017). “Disbiosis como factor determinante de enfermedad oral y sistémica: importancia del microbioma” [Dysbiosis as a determining factor of oral and systemic disease: the importance of the microbiome]. Clin. Vol. 149(7): 305-309. URL: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-medicina-clinica-2-articulo-disbiosis-como-factor-determinante-enfermedad-S0025775317304414

(3) Icaza-Chávez, M.E. (2013). “Microbiota intestinal en la salud y la enfermedad” [Gut microbiota in health and disease]. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. Vol. 78(4): 240-248. URL: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0375090613001468

(4) Narula, N. et al. (2021). “Association of ultra-processed food intake with risk of inflammatory bowel disease: prospective cohort study”. BMJ; 374: n1554. URL: https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1554

(5) Rinninella, E. et al. (2019). “Food components and dietary habits: keys for a healthy gut microbiota composition”. Nutrients. Vol. 11(10): 2393. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6835969/