The Economist addresses the challenges, expectations, controversies and problems of increased life expectancy.

From an individual’s point of view an extended life is often seen to be attractive, but from the point of view of society as a whole, certain controversies and possible sociological and economic problems can appear which include: sustainability of retirement pensions, the present retirement age, the ageing workforce; the ‘lock-out’ which affects professional positions of responsibility in a generation that remains active and healthy and does not seem willing to allow the next generation to replace them…

Neolife medical management

The increase in life expectancy in modern societies has exponentially increased the number of centenarians (including over-centenarians): Is this a problem?

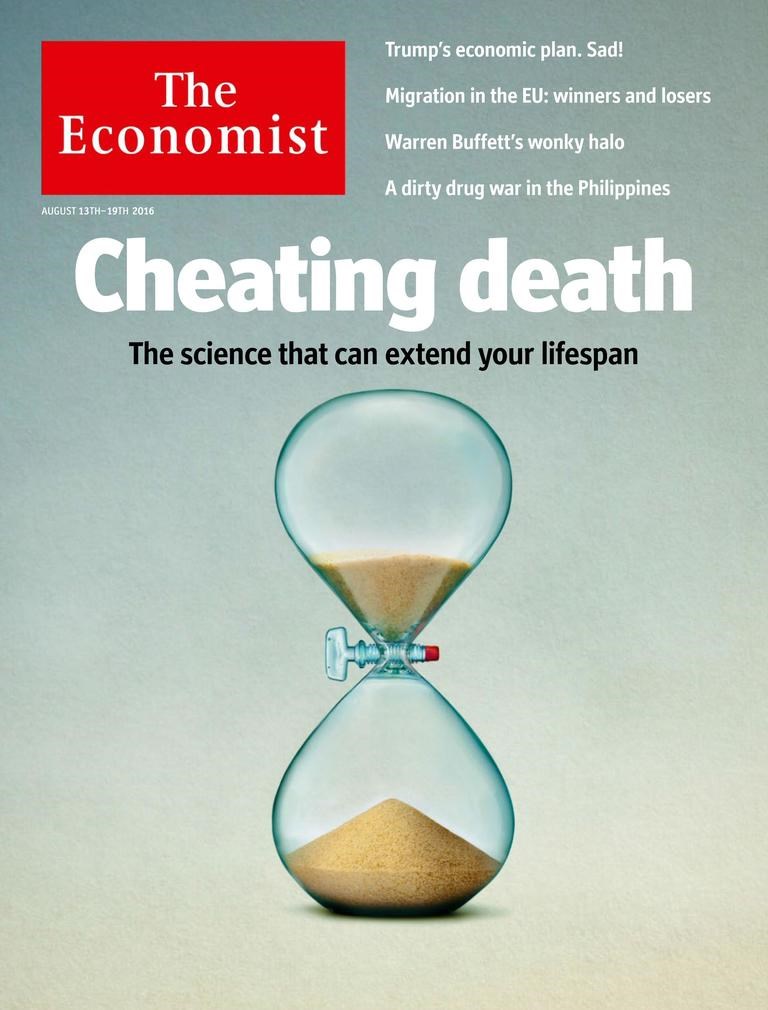

It is less and less surprising to find articles in general publications about the latest advances in the science of longevity (see the article in the Neolife blog titled “Healthy Longevity, a trending topic”, part I and part II). Last summer the subject was discussed in The Economist (1), with the title “Cheating Death, the science that can extend your lifespan”, which translated loosely as “side-stepping death, the science that can help extend your life expectancy”. This article is a useful and beneficial read that concisely addresses, in a detailed manner, the current situation, the challenges, expectations, controversies and problems that are going to arise alongside the increase in the maximum life expectancy as we as a society approach a society which includes people of 120 years old and where the average life expectancy is 100 years.

During the twentieth century the average life expectancy increased by about 30 years in developed countries from approximately 50 to 80 years. For the most part this was due to the advances in public hygiene, water treatment, improvements in nutrition, improvements in housing and advances in medicine particularly in antibiotics and surgery. From this point forward, the increase in life expectancy will not only maintain the average age (currently it is 83.3 years in Spain), but medical advances will also increase the maximum life expectancy, that is to say, the maximum number of years we can expect to live. For now the record remains with Jeanne Calment, a French woman who died in 1997 aged 122 years old but she is expected to be overtaken in the coming years by an upcoming group of ‘over-centenarians’ people who have benefited greatly from modern medicine (5,760 in 2000 compared to 14,487 in 2015 in Spain). The current group of centenarians (including those over 100) have benefited from many of the advances which we have witnessed during the 20th century, but the real revolution will come when the “millennials” who were born in the 1980s and 1990s who have been treated with drugs and modern therapies specifically designed to extend their life reach their centennial years.

From an individual’s point of view an extended life is often seen to be attractive, but from the point of view of society as a whole, certain controversies and possible sociological and economic problems can appear which include: Who will have access to the longevity treatments? Will selection be dictated by an individual’s economic level? Will there be different social groups who each have their own expected lifespan?

These are some of the more evident questions in the face of such “artificial” increase in our longevity. Notwithstanding the above there are serious problems which may arise regarding how best to maintain retirement pensions, the present retirement age, sustain an ageing workforce, or prevent the ‘lock-out’ effect in professional positions of responsibility in a generation that remains active and healthy and does not seem willing to allow the next generation to replace them (conspiracy of Methuselah). On the other hand, we will approach 50 years not with the expectation of ageing healthily as we do now, but with the expectation of building a new life, starting a new university career, a new profession, a new marriage, perhaps even starting a new life as a mother or father…

healthy aging will allow us to live for more than 100 years.

In the years to come if we were able to completely overcome cardiovascular disease and cancer, the average life expectancy would extend a further 3 to 6 years; therefore, by applying this data to our country, the life expectancy would change from the current 83.3 to 87 or 90 years.

Caloric restriction, metformin, rapamycin, resveratrol, gene therapy and stem cells, the present and future of Preventive Anti-ageing Medicine.

In previous blogs we have previously commented about the differences between healthy ageing medicine and genuine anti-ageing medicine. Genuine anti-ageing medicine is medicine designed to not only lengthen your disease-free life, but also your maximum life expectancy. Today we must focus on taking positive steps within our control such as caloric restriction which is the best known technique for increasing longevity: the process has been shown to work in rodents and it is possible in large primates, but we still do not know if it will be truly effective in humans; furthermore, the implementation is painful and involves a level of sacrifice. However, the future will come hand in hand with new and not so new drugs, such as gene therapy and stem cells.

Until just a few months ago it was unthinkable that the health authorities would be considering the existence of an anti-ageing drug, since ageing is not a disease, or is it?. More and more authoritative voices are changing their opinion on the concept that ageing is itself a disease that can be prevented, or at least postponed. Along this line of thought, the FDA have recently approved the first clinical trial to combat ageing by using metformin. But rapamycin or resveratrol are also in the race to be part of a new line of anti-ageing drugs.

As advances in genetics are made these are accompanied by those who are searching for more such as Human Longevity and Craig Venter (the first scientist to sequence the human genome) as he searches for the genes responsible for determining longevity in humans or Bioviva Sciences and Elisabeth Parrish, who is providing genetic treatments to activate telomerase and inhibit myostatin, two actions that are understood to extend life, at least in mice. The world of regenerative stem cell therapy is not far behind in their search for cell repair and cell rejuvenation therapies.

Like the article in The Economist, August was the month when the RAAD Festival (The Revolution Against Aging and Death) took place, a sort of pseudoscientific event held in California that attracts hundreds of participants interested in the latest developments in longevity. Attendees included: Aubrey de Gray, Bill Andrews, Suzanne Sommers, Liz Parrish, Ray Kurzweil, etc. Our friend and collaborator Steve Matlin, CEO of Life Length was also at the event. Life Length markets the use of telomeric research and is furthering steps overseas due to increased demand and expectation in the US. RAAD fest attendees may not be able to benefit from all of the anti-ageing therapies, but there is no doubt that their children and grandchildren will.

And while we wait for the arrival of these therapies in the future, let us continue to push forward with Neolife’s protocols Preventative, Proactive, Predictive and Personalized Medicine in our efforts to achieve healthy ageing until the end of our days.