Is depression a biological disorder or a response to a psychosocial stress that the individual cannot cope with? Exogenous or reactive depression has an easily identifiable cause; however, endogenous depression has no obvious cause.

This is why it is considered a biological dysfunction, where certain neurotransmitters such as serotonin, and more complex systems, like the central nervous system and the immune system, as well as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, play a central role in its development.

Dr. Débora Nuevo Ejeda – Neolife Medical Team

Depression: the pandemic of the future

An estimated 300 million people worldwide suffer from depression or some mood disorder, and nearly 90% are untreated.

Spain is the 4th country in the European Union with the most cases of depression, according to the 2017 National Health Survey. One in 10 adults and one in 100 children suffer from mental health problems. One in 10 adults turn to benzodiazepines and one in 20 take antidepressants. The economic cost it entails is clear to see.

And the worst is yet to come. In the last economic crisis that rocked Spain, mood disorders increased by 20%, anxiety disorders by 8%, and alcohol abuse by 5%.

The toll this disease has on the general population is obvious, as well as its importance to scientific research, which is why the study of its possible causes and potential treatments is a trending topic, even though some of its pathological mechanisms remain a mystery.

Possible causes of depression

Depression undoubtedly responds to multiple factors. Among its causes, we may highlight:

- Genetic factors: Some specific genes have been linked to the development of certain mood disorders.

- Chemical factors: Alterations in the neurotransmitters produce imbalances that cause alterations at the level of the central nervous system and the psyche.

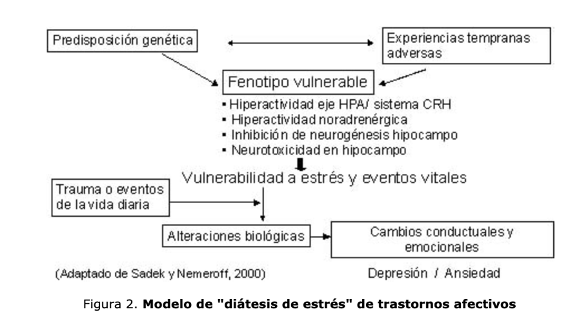

- Psychosocial factors: These are perhaps the most studied and known factors, on which we will focus less in this article. There is one exception, however: the relationship between stress, both physical and emotional, and the activation of an inflammatory domino effect that leads to a clinical picture that is typical of an infection but also the appearance of, for example, anhedonia and dysphoria, clear symptoms in a depression.

Genetic factors:

The endogenous depression and major depressive disorder have a more significant genetic influence. The risk of developing it is higher in first degree relatives, even regardless of environmental factors and education. Some potential markers for mood disorders have been located in chromosomes 4.5, 11, 18, 21, and X.

A clear example of this genetic relevance is the functional polymorphism that exists in the serotonin transporter gene promoter region, which modulates the influence of stress on depression.

Each person inherits two copies of this gene (called SLC6A4), one from each parent. In subjects who received at least one copy with the short variant, images taken with scanners during emotional stimuli, such as fear, show increased activity in the amygdala of the brain, which results in more sensitivity to situations that cause stress. Other studies have collected increased suicidal tendency and more depressive symptoms in patients with one or more copies of the short allele of this gene.

Chemical factors:

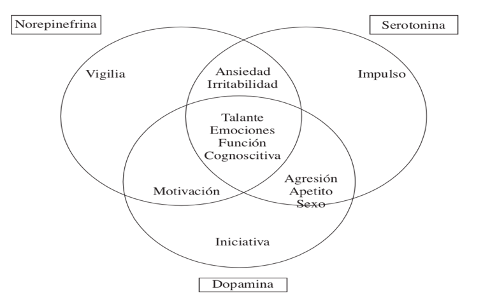

It has been shown that abnormal levels of aminergic neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine), which act on the neurons in the central nervous system, may play a key role in the physiopathology of depression.

Serotonin

Serotonin exerts an important action on behavior, movement, pain perception, sexual activity, appetite, cardiac functions, endocrine functions, and in the sleep-wake cycle.

Most of this neurotransmitter is produced in the raphe nuclei, located in the brain stem between the bulb and the bridge.

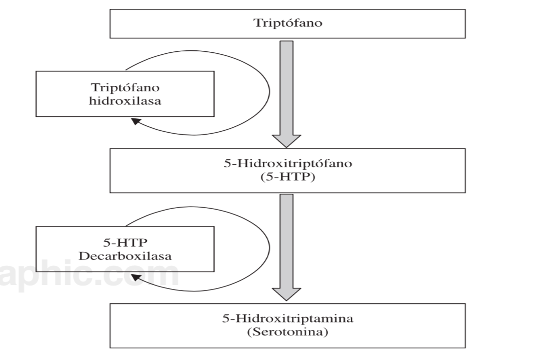

Serotonin is produced from the amino acid Tryptophan, which is transported through the blood-brain barrier by the large amino acid transporter. This transporter also moves other amino acids and the tryptophan has to compete with them. Therefore, the concentration of tryptophan also depends on the concentration of other amino acids.

Norepinephrine (NE)

In the brain stem, we find the locus coeruleus, where norepinephrine is generated. This locus coeruleus has the function of pacemaker, and its neurons increase its activity during wakefulness and situations of stress. Therefore, it makes sense that chronic stress leads to reactive depression. Norepinephrine reserves in the brain tend to run out and maintain this state of depression.

A deficit of this neurotransmitter and imbalance with serotonin may even cause depressive, unipolar, or bipolar psychosis. The treatment of these disorders is therefore aimed at improving NE activity.

The precursor to NE is the amino acid tyrosine, which is first to be converted into dopamine.

Dopamine

Dopamine is generated in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra and other neurons in the midbrain. It is primarily an inhibitory neurotransmitter and helps to maintain alertness. It is synthesized from tyrosine by the same pathway as norepinephrine.

While serotonin and norepinephrine exert more influence on behavioral patterns and mental function, dopamine is more involved in motor function.

The interaction between these three neurotransmitters is considered so important that 50 years ago the so-called “monoamine hypothesis in depression” was established.

Monoamine oxidase is an enzyme that regulates the metabolic degradation of serotonin and norepinephrine in the nervous system. This may explain the beneficial effects of tricyclic antidepressants and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI). The idea that consuming tryptophan-rich foods within the diet may also be helpful in combating depression or even diminishing its onset has also been postulated.

Initially, this hypothesis was based on the idea that depression may be caused by a defect in the function of these monoamines in specific brain locations, so that antidepressants exerted their effects by increasing these monoamines in synaptic terminals.

Chronic smoking has been shown to inhibit monoamine oxidase B, an enzyme involved in the degradation of dopamine and monoamine oxidase A. This explains part of the antidepressant action that nicotine possesses.

Moreover, some laboratory and clinical studies show the involvement of nicotinic receptors in complex brain functions and also in the development of various neuropsychiatric diseases such as Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s, some types of epilepsy and schizophrenia. In these pathologies. these nicotinic receptors are decreased, and smoking may be considered a form of self-medication in schizophrenia, attention deficit disorder, and also depression.

Other studies suggest that depression may facilitate alcohol abuse and that nicotine would help reduce this use of alcohol. It has been shown in experimental models that chronic administration of high levels of nicotine, decreases alcohol intake and increases locomotive activity but also aggressiveness.

However, other harmful effects of nicotine and tobacco prevent them from being used therapeutically. Drugs like duloxetine, sertraline, and reboxetine, antagonists of specific nicotinic receptors (nAChRs), have provided effective treatments and new routes towards the generation of more effective antidepressants.

In upcoming articles, we will try to define depression and its biochemical and neuroanatomical bases, and then focus on the important role that stress and inflammatory processes have in its development.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Escobar A. Neurobiología de la depresión [The neurobiology of depression]. In: Velázquez Moctezu- ma J, Ed. Temas Selectos de Neurociencias III. UA Nueva teoría sobre la depresión: un equilibrio del ánimo entre

(2) Leslie Alejandra Ramírez, Elsy Arlene Pérez-Padilla. El sistema nerviosos y el inmunológico, con regulación de la serotonina-quinuerina y el eje hipotálamo-hipofiso-suprarrenal [The nervous system and the immune system, with regulation of serotonin-quinuerin and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis]. Biomédica 2018;38:437-50

(3) Leyla Guadarrama,1,2 Alfonso Escobar,3 Limei Zhang1 . Bases neuroquímicas y neuroanatómicas de la depresión [Neurochemical and neuroanatomical bases of depression]. Rev Fac Med UNAM Vol.49 No.2 March-April, 2006

(4) Albert, P.R., 2015. Why is depression more prevalent in women? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 40, 219–221.

(5) American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5TM. 5th ed. Arlington, VA, US, Inc.: xliv, 947–xliv, 947