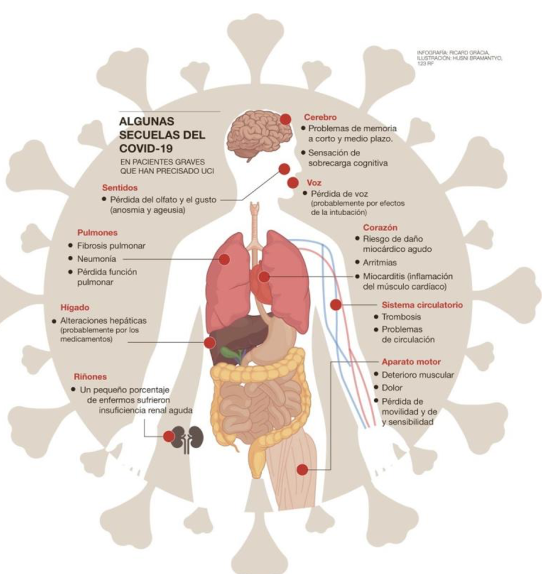

The impact of coronavirus (or COVID-19) on the population can continue for a fairly long period of time. The symptomatology that we describe in the first part of this article (cough, difficulty breathing, weakness, headache, digestive problems, etc.) can persist well beyond 12 weeks. This is a clinical condition that has come to be called Subacute Coronavirus Disease, or Long COVID.

On many occasions, these patients which are not in the acute phase (or “danger phase”) are considered to be “cured.” However, all the symptomatology that they present at different levels makes it difficult for them to resume their normal life, or at least under usual conditions and/or normal performance levels. Therefore, at Neolife we believe it is important to provide treatment and support to facilitate, as much as we can, a recovery that is as complete and as quick as possible.

Dr. Débora Nuevo Ejeda – Neolife Medical Team

But… what do we consider a “normal recovery?”

Patients admitted to the hospital after a coronavirus-related pneumonia may present difficulties in recovery and said recovery may have a longer duration than usual. However, normally within 12-14 weeks the symptoms have improved. In any case, everything depends on the severity of the disease, existing comorbidities, and the fragility of the patient.

The evolution considered as “normal” that we can expect is as follows:

- At 4 weeks, muscle pain, chest pain, and expectoration are usually significantly reduced.

- Between 4 and 6 weeks, the cough and trouble breathing usually improve.

- After 3 months, most symptoms have disappeared but asthenia (or weakness) may persist.

- At 6 months, it is usual for the entire disease to have been resolved — unless the patient presents complications.

For all those patients who continue to present symptoms after a time that is considered as “normal,” we will try to offer an explanation, support, and treatment to favor optimal recovery.

Management of respiratory symptoms

The Society of Thoracic Medicine defines chronic cough as a persistent cough for more than 8 weeks. Until that time, and unless there are signs of serious infection or other complications such as pleuritic pain, cough should be managed with respiratory exercises and appropriate medication when necessary (such as PPIs when reflux is suspected).

Dyspnoea (or difficulty breathing) may be common after a coronavirus respiratory infection. Severe respiratory distress is uncommon in non-hospitalized patients; however, if it occurs, it requires a preferred referral to emergency or specialized medical services.

Both dyspnea and cough can improve significantly with breathing exercises.

A pulse oximeter is very useful for monitoring symptoms and recovery after COVID-19.

Hypoxia reflects a problem with the diffusion of oxygen and is one of the typical symptoms of respiratory problems associated with coronavirus. This hypoxia can be asymptomatic (also called silent hypoxia) or manifest as an increase in respiratory work or be a reflection of an associated secondary pathology such as bacterial pneumonia or pulmonary thromboembolism.

Monitoring of oxygen saturation for 3-5 days may be especially useful in patients who continue with dyspnea after the acute phase. In some cases, a desaturation test is also recommended in those patients who suffer from dyspnea with exertion or despite having basal oxygen saturations above 95%. This test consists of measuring saturation at rest and after walking 40 steps over a flat surface and sitting and getting up as quickly as possible for 1 minute. A 3% fall in saturation is considered abnormal and must be studied.

Saturations between 94-98% are considered normal, and saturations below 92% may require oxygen therapy.

If recovery is spontaneous, in about 6 weeks no rehabilitation programs are needed. Patients who have had lung damage can benefit greatly from this restorative treatment, defined as a multifaceted intervention based on a personalized assessment and treatment that includes training and behavior modification to improve the physical and psychological condition of these patients with respiratory disease. This may include videos programs, tele-assistance, etc.

Asthenia (weakness)

The severe asthenia (or weakness) that some patients describe with Long COVID is reminiscent of the chronic fatigue described after SARS, MERS, and other pneumonias.

There is no evidence of the usefulness of drug or non-drug therapy to reverse this fatigue.

Additional causes such as deficiencies of certain vitamins, minerals, and/or trace elements that favor the feeling of weakness should be investigated. A hormonal study can also be of great help. The stress of coronavirus infection can alter some hormonal axes.

As for exercise, a gradual return to normal life is recommended. There is controversy about the impact of exercise on chronic fatigue. It is recommended to start exercise gradually and stop it if the patient has fever, dyspnea, severe asthenia, or significant muscle pain.

A physical therapist’s guidelines for restarting physical exercise can be critical in order to do so in the most beneficial way possible.

Cardiovascular complications and their management

Probably 20% of patients admitted have significant cardiac complications and an even greater percentage have cardiological involvement without being aware of it.

These cardiopulmonary complications include myocarditis, pericarditis, infarction, arrhythmias, and pulmonary thromboembolism. They can appear during an active acute COVID infection or weeks later, during the so-called Long COVID disease. They are more common in patients who already have some type of cardiovascular disease. Several pathophysiological mechanisms have been proposed to explain their development, such as viral infiltration, an inflammatory process with microthrombosis, and poor regulation of ACE-2 receptors.

- Chest pain:

Chest pain is quite common in Long COVID. The main difficulty that arises is to differentiate between musculoskeletal (or mechanical) pain and specific chest pain. Diagnosis should be approached in the same way as any chest pain: by reviewing the complete medical history with all previous conditions, by looking at cardiovascular risk factors, and with a thorough physical examination. If there are doubts, the patient should be referred to a specialist for specific tests (ECG, cardiac MRI, echocardiogram, etc.) and relevant treatment.

Treatment of mechanical pain consists of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs as needed.

- Pulmonary thromboembolism:

As is well known by now, COVID 19 is considered a proinflammatory state and a state of hypercoagibility with an increased risk of thrombotic phenomena.

Most hospitalized patients receive anticoagulation treatment during their hospital stay or in the ICU. However, post-COVID anticoagulation recommendations vary greatly. A large proportion of patients with moderate or severe disease also receive an anticoagulation regimen that covers at least 10 days after hospital discharge. The duration of treatment with heparin will also vary depending on the degree of mobility the patient has. Those more limited patients will need longer treatments, since immobilization is also a risk factor for thrombosis.

If they are diagnosed with a thrombotic episode, it is treated following the usual guidelines and controls.

- Ventricular dysfunction:

Systolic dysfunction and heart failure after COVID should be managed following conventional guidelines. Intense cardiovascular exercise should be avoided during the first 3 months, especially after myocarditis or pericarditis. These patients should be periodically checked by the specialist.

Again, guidance and follow-up from a physiotherapist is essential in these patients when resuming exercise.

Digestive involvement

The digestive system is one of the systems most commonly affected by the coronavirus. Many patients have diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, etc. These conditions especially tend to last long. Thus, it is not strange that patients continue to present intestinal transit alterations and abdominal discomfort many weeks after acute infection. This also leads to malabsorption and deficiency of proteins, minerals, and some vitamins.

It is necessary to investigate a potential bacterial overgrowth made stronger by the infection itself and the antibiotic and corticosteroid treatment used in the management thereof. The alteration of the intestinal flora that this causes perpetuates the problem.

Repopulating the intestinal flora with probiotics, making specific dietary changes, and supplementing the deficits caused can favor recovery and the improvement of symptoms.

Neurological involvement

Complications like stroke, vertigo, encephalitis, and neuropathies have been described during or after an acute COVID infection, although they are uncommon. If suspected, they should be evaluated by a neurologist.

Other more nonspecific symptoms which tend to appear with dyspnea and cough are headache, dizziness, and confusion and they should equally be managed in a conventional way. Other added causes that can chronify the condition should be investigated, such as vitamin deficiency (suboptimal vitamin D or low levels of B vitamins), iron deficiency, etc. They should be treated symptomatically when necessary, with specific analgesics and supplements.

- Anosmia and ageusia: loss of smell and taste

4 out of 10 patients experience loss of smell and/or taste. While patients with irreversible loss of smell are not yet known and it is normal to recover said sense in 2 weeks, there are patients who after 8 weeks are still unable to distinguish certain odors.

Young patients and those with milder forms of the disease who do not require hospital admission are most affected by this loss.

There are various olfactory training techniques, rehabilitation of the sense and olfactory memory, that can be guided by professionals and help a lot to recover these senses.

Mental health and wellbeing

There is much talk about the consequences that COVID is having on mental health; stress, anxiety, and other alterations stemming from the breakdown of routine, loneliness, isolation, and social exclusion. There have also been increased sleep problems and the appearance of post-traumatic stress disorder, especially in healthcare personnel and caregivers. Psychological support can be of great help. Using scales like the ones we routinely use in our clinic can also be a great support to assess the magnitude of the problem.

Many papers are now focused on studying the benefits of melatonin on these conditions, both because of its role regulating chronobiotic agents and because of its high anti-oxidant power.

As we have seen, Subacute Coronavirus Disease or Long COVID can encompass many symptoms that significantly limit the quality of life of the patients affected. Identifying issues and providing support and treatment are critical to reducing the impact of COVID over the medium and long term.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Geddes L. Why strange and debilitating coronavirus symptoms can last for months. New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg24632881-400-why-strange-and-debilitatingcoronavirus-symptoms-can-last-for-months/.

(2) …Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x. pmid: 32529595

(3) Phillips M, Turner-Stokes L, Wade D, et al. Rehabilitation in the wake of Covid-19—A phoenix from the ashes. British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2020. https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/covid-19bsrmissue1-published-27-4-2020.pdf.

(4) Assaf G, Davis H, McCorkell L, et al. An analysis of the prolonged COVID-19 symptoms survey by Patient-Led Research Team. Patient Led Research, 2020. https://patientresearchcovid19.com/.

(5) Callard F. Very, very mild: Covid-19 symptoms and illness classification. Somatosphere 2020; https://somatosphere.net/2020/mild-covid.html/.

(6) Garner P. Covid-19 at 14 weeks—phantom speed cameras, unknown limits, and harsh penalties. BMJ Opinion [blog]. 2020; https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/06/23/paul-garner-covid-19-at-14- weeks-phantom-speed-cameras-unknown-limits-and-harsh-penalties/.

(7) COVID Symptom Study. How long does COVID-19 last? Kings College London, 2020. https://covid19.joinzoe.com/post/covid-long-term?fbclid=IwAR1RxIcmmdL-EFjh_aI-.